The controversy that broke out in February 2018 over what Russian president Vladimir Putin did or did not say in a meeting in 2006 during a gathering with Shell-managers (minus Halbe Zijlstra) at his dacha has raised significant issues: What does the Kremlin chief really think about the geographic and geopolitical extent of Russia? Hannes Adomeit did some close reading of Putin's public statements and concludes that restoring control over the post-Soviet states is his aim.

One could easily agree, as Halbe Zijlstra claimed, that Putin counts the Slavic countries of ‘Russia, Belarus and Ukraine’ to be part of it but how valid is it to believe that they also included ‘the Baltic States’ and that ‘Kazakhstan was nice to have’? Prime minister Mark Rutte, when initially defending his foreign minister, asserted that there was ‘no dispute about the content of the story’. But apparently there is some at least about Kazahkstan because the former CEO of Shell Jeroen van der Veer did ‘not recall’ how he had mentioned the specific countries to Zijlstra but doubted whether ‘nice to have’ was a term that himself would have would used.

Former Dutch minister of Foreign Affairs Halbe Zijlstra claimed he heard Putin speak about 'Greater Russia'. Photo Roel Wijnstra

Former Dutch minister of Foreign Affairs Halbe Zijlstra claimed he heard Putin speak about 'Greater Russia'. Photo Roel Wijnstra

Most importantly, however, is the question of whether Putin’s purported ‘Greater Russia’ idea was merely, as Van der Veer thought, ‘historically intended’ or whether it is of current political significance, whether it is gratuitous nostalgia or has serious practical geopolitical implications.

Precise wording

In order to provide a correct assessment of what Putin may have meant it would be useful to know the precise wording, including the Russian original of the translated word of ‘Greater Russia’. First and foremost, there is a problem of translation: In English, whereas ‘great’ has a qualitative dimension as, for instance, in ‘great achievement’ or, indeed, in Putin’s striving for Russia to be restored as a Great Power (velikaya derzhava), the term ‘Greater’ is employed for geographical constructs. As for its historical aspects, it is doubtful that he thought of the official designation of the European part of Tsarists Russia from the second half of the 17th century onwards, namely Velikaya Rossiya, literally Great(er) Russia, or for that matter, Velikorossiya – ‘Great(er) Russia’, in one composite word – employed from the 19th to the beginning of the 20th century.

The historical aspects, however, appear to play some role in Putin’s thinking. They certainly do in the current-day narratives. Thus, in his justification of the annexation of the Crimea and in an obvious appeal to Berlin to accept this violation of international law, he spoke of Russia as a ‘divided people’ and reminded the Germans that ‘our country supported the sincere striving of the Germans for national unity’ and that he hoped that Germany would now ‘support the efforts of the Russian world, of historical Russia, to restore unity (yedinstvo)’. However, he left open the question as to the boundaries of Russia in what century.

In the context of Russia’s military intervention in eastern Ukraine, Putin again ventured into history by resurrecting the term Novorossiya (New Russia). This czarist-era term referred to a governorship administering a large swath of modern-day Ukraine that Catherine the Great wrested from the Ottomans and Cossacks at the end of the 18th century. For Putin’s separatist project in eastern Ukraine it was evidently meant to unite the self-declared separatist republics of Donetsk and Luhansk in one entity and to lay the basis for their expansion via Mariupul, Mykolaiv and Odessa to Transnistria. One year later, however, the Kremlin abandoned the terminology.

The term Novorossiya (New Russia) was resurrected in 2014 during the Russian military intervention in East Ukraine. Map Wikipedia

The term Novorossiya (New Russia) was resurrected in 2014 during the Russian military intervention in East Ukraine. Map Wikipedia

Former Soviet Union

Whatever the significance of Putin’s excursions into czarist history, it is extremely doubtful that such historical constructs provide a precise geographic and geopolitical frame of reference that determines his policies. What, in contrast, is well nigh incontrovertible is that the conceptual point of reference for him is the former Soviet Union. This concerns both its geographic extent as well as its status as a superpower on a par with the United States. Evidence of this can be provided both from Putin’s statements as well as from his policies.

'What was the Soviet Union? It was Russia, only under a different name'

The most telling give-away is the answer to the rhetorical question he put in October 2011 when he was getting ready for his third term in office as president. ‘What was that, the Soviet Union?’, he asked, to which he replied that it was simply ‘Russia but only under a different name’. That understanding of Russia is consistent with his view of the collapse of the Soviet Union as being a ‘national tragedy of immense proportions’ and ‘a major geopolitical catastrophe of the [20th] century’. (It should, indeed, be ‘major’, krupneyshaya, which he used, rather than ‘the greatest’, samaya krupnaya, catastrophe which he didn’t.) Important to note in this context is the term ‘geopolitical’, which relegates the human dimension to a secondary position. The collapse of the Soviet Union, Putin continued, had been ‘a real drama for the Russian people. Tens of millions of our co-citizens and compatriots found themselves outside of Russian territory’.

Sphere of influence

The implication of Putin’s regret about the dissolution of the Soviet Union has sometimes been interpreted as having as its practical consequence the endeavor for the restoration of the USSR in its then existing legal and constitutional form. What is really at issue, however, is Putin’s attempt at the restoration of control over the domestic political and economic affairs as well as the foreign policy orientation of the post-Soviet states. It is the Kremlin’s claim for possessing and having to safeguard a sphere of influence and the assertion of special interests on the territory of the former USSR.

Such claims are firmly rooted in the Realist School of international relations. That rather simplistic theory posits that international relations are to be understood as some kind of ‘grand chessboard’ in which ‘zero-sum games’ (the loss of one side is the gain of the other) are played among sovereign state actors; where the ‘balance of power’ and the ‘correlation of forces’, understood primarily in military terms, matters; and where no ‘power vacuum’ could exist. Putin has explicitly endorsed such theorems and applied them to the post-Soviet geopolitical space. ‘In international relations’, he told his diplomats in 2004, ‘there can be no vacuum. If Russia were to refrain from [pursuing] an active policy in the CIS [Commonwealth of Independent States], or even embark on a groundless pause, that would inevitably lead to nothing other than that this political space would resolutely be filled by other, more active states.’

Yeltsin's near abroad

The consideration of the post-Soviet space as an exclusive Russian sphere of influence, however, is not a phenomenon that suddenly cropped up in the Putin era. That pretension appeared early on in the Yeltsin era. Verbally it gained currency in the term of the Near Abroad; institutionally, it found its expression in the CIS; and politically, it took the form of what in the West was called the Yeltsin Doctrine for Eurasia, the Russian equivalent of the Monroe Doctrine of the United States for the Western Hemisphere. Thus, in February 1993 Yeltsin said that Russia ‘continues to have a vital interest in the cessation of all armed conflicts on the territory of the former USSR’, adding that ‘the moment has come when responsible international organizations, including the United Nations, should grant Russia special powers as a guarantor of peace and stability in the region of the former Union’.

Yeltsin wanted 'special powers' in the region of the former Soviet Union

The Yeltsin Doctrine is just one of the indications that, by the mid-1990s, the ‘new’ Russia had begun to turn away from the Euroatlantic course as pursued by foreign minister Andrey Kozyrev – away from the visions of ‘Europe Whole and Free’ and the formation of a ‘Euroatlantic Community from Vancouver to Vladivostok’ to some ‘Eurasian’ orientation. Yeltsin was increasingly yielding to the pressure and demands by a powerful a national-patriotic opposition centered on conservative political forces, chekisty, that is, present and previous members of the secret services, the military, the military-industrial complex and a ‘red-brown’ coalition in the Duma of unreconstructed communists and strident nationalists.

Bron: CIA World Fact Book

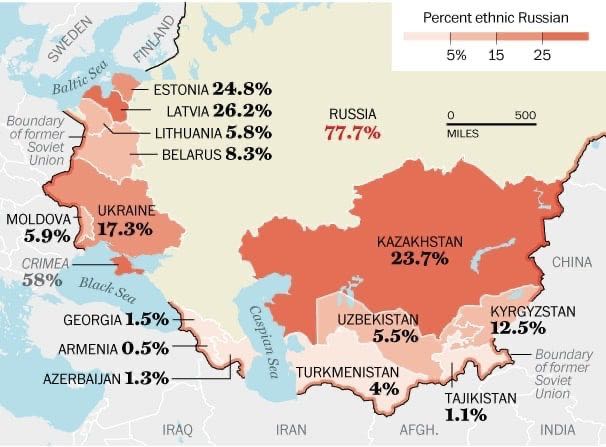

The utilization of the Russian minorities as an instrument for the realization of the special interests on post-Soviet space is also not a Putin invention but goes back to the Yeltsin era. In February 1994, the Russian foreign ministry published a ‘program’ for the purpose of ‘protecting the rights’ not only of the 25 million ethnic Russians (according to the 1989 and last Soviet census) living outside the Russian Federation but also those of the larger number of ethnically non-Russian but culturally assimilated citizens in the newly independent states, the ‘Russian speaking’, or russko-yazychnaya, group of persons, thereby increasing the number of people eligible for Russian ‘protection’ to more than 30 million. Evidently with the aim of their ‘protection’, the defense ministry called for the maintenance or the creation of new military bases.

NATO and EU

The pretension of Russia having a legitimate claim to a special sphere of influence on post-Soviet space rules out membership of any of the former Soviet republics in NATO. This position, too, did not appear suddenly in the Putin era. Whereas, in January 1992, Yeltsin had stated in the UN Security Council that Russia considered the United States and the West no longer as adversaries but as ‘allies’, in November 1993 a widely publicized study by the Russian Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR) returned to inimical images that are current in Russia to this very day. It characterized NATO as the ‘biggest military grouping in the world that possesses an enormous offensive potential’; called the alliance an organization ‘wedded to the stereotypes of bloc thinking’; and expressed strong opposition to NATO membership of the Central and Eastern European countries. Two months later, Yeltsin's press spokesman, reacting to Lithuania’s request for membership in NATO, warned that the expansion of NATO into areas in ‘direct proximity to the Russian border’ would lead to a ‘military-political destabilization of the region’.

Russia’s claim to a special sphere of influence and interest, however, not only precludes membership of the post-Soviet states in NATO but also their close alignment with the European Union. This was clarified at the transition point of the Yeltsin era to Putin. In June 1999, in its Common Strategy towards Russia, the EU had offered the country a ‘strategic partnership’ on the basis of common European values. In its reply of October of the same year handed by Putin to the EU troika in Helsinki in his then capacity as prime minister, Moscow stated its position as follows: EU enlargement had an ‘ambivalent impact’ on EU-Russia cooperation; as a ‘Euro-Asian state’ and ‘the largest country of the CIS’ Russia had a ‘special status and advantages’ in this area; it would use the positive experience of EU integration ‘to enhance integration in the CIS’, counteract ‘any attempts to hamper economic integration in the CIS’, ‘oppose “special relations” by the EU with individual CIS countries to the detriment of Russian interests’, and reserve the right ‘to refuse agreement to the extension of the PCA [Partnership and Cooperation Agreement]’ to EU candidate countries.

Baltic States - a challenge

The EU candidate countries, of course, included the three Baltic States − Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania – but Moscow had no intention of excluding the Russian minorities there from ‘protection’. The Baltic countries, however, presented special challenges. On the one hand, the Russian diaspora in Latvia and Estonia was especially numerous amounting, according to the 1989 census, to 34 per cent in the former and 30 per cent in the latter country. This appeared to provide significant opportunities for exerting influence on the domestic and foreign policies of these two countries. (In Lithuania there existed − and exists − less opportunity as only 9 percent of the population in 1989 had declared themselves as being ethnically Russian.) On the other hand, in contrast to all the other ex-republics of the USSR, the Baltic States had enjoyed independence between the two world wars, a fact recognized under international law also by the Soviet Union. They were the first republics to declare and achieve independence from the USSR, and they adamantly refused membership in the CIS.

Yeltsin's advisers deplored abandonment of military bases and strategic objects in the Baltics

The Russian minorities also have not been too keen to welcome Moscow’s ‘protection’, and certainly they have shown little inclination to emigrate to Russia. Thus, the Kremlin under Putin has increasingly attempted to use ‘hard power’ such as military pressure, based on the modernization and expansion of military forces in the Northwestern Military District and Kaliningrad, as a lever. The proclivity to use this instrument, too, was evident in the Yeltsin era, and it expressed itself in regrets. In October 1997, the Russian Council for Foreign and Defense Policy deplored that possible leverage had gratuitously and unwisely been given away: ‘Maintaining Russian military contingents […] and important strategic objects and bases on Baltic territory would have helped to avoid many problems. It would have influenced the citizenship debate in the Baltic states and the general context of Russian-Baltic relations. The Baltic-NATO problem would have looked much different. But this opportunity was missed by the Russian diplomacy − almost [it seems] on purpose.’

What, then, if any, is the difference between the attitudes and policies concerning the Kremlin’s assertion of special interests on post-Soviet space in the 1990s and after 2000?

From pretentions to actions

Under Yeltsin, the pretensions essentially were just that. They largely remained without major consequences because the country found itself in weak position. Under Putin, as Russia’s economic performance measurably improved and the confidence of its foreign policy security elite increased, the pretensions took on practical political and military significance. They were prefaced by serious warnings. A major example of this was Putin’s speech at the 43rd Munich Security Conference in February 2007 where he called NATO’s eastward enlargement a ‘serious provocation’.

'NATO on our borders will be seen by Russia as a direct threat to our country's security'

In April of the following year, in the context of the April 2008 NATO summit and the meeting of NATO-Russia Council in Bucharest he issued stern warnings against NATO if it were to offer Membership Action Plans to Ukraine and Georgia. On April 3, on the very day when Putin arrived in the Romanian capital, he told Abkhazia’s and South Ossetia’s de facto leaders that Russia would take ‘not declarative, but practical steps’ in their support. On the following day, at the council summit and having in mind both Ukraine and Georgia, he stated unequivocally: ‘The presence of a powerful military bloc on our borders, whose members are guided, in particular, by Article 5 of the Washington treaty, will be seen by Russia as a direct threat to our country's security’. The territorial integrity of Georgia was put in question.

Georgia and Ukraine

Putin warned US president George W. Bush that if Georgia moved toward NATO membership, Russia might respond by recognizing Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Russian ambassador to NATO Dmitry Rogozin warned that attempting ‘to push Georgia into the Western alliance is a provocation that could lead to bloodshed’. Membership of the country in NATO would be ‘the end of Georgia as a sovereign state’. Four months later, it was not the offer of a membership action plan to Georgia that led to the recognition of the two separatist republics but Georgian president Mikheil Saakashvili’s attack on South Ossetian Tskhinvali. That unwise, militarily and politically ill prepared step, provided Russia with the justification for massive military intervention.

The Georgian and American president at the NATO summit in Bucharest in 2008. Putin warned president Bush not to let Georgia become a member of NATO. Photo White House

The Georgian and American president at the NATO summit in Bucharest in 2008. Putin warned president Bush not to let Georgia become a member of NATO. Photo White House

Concerning Ukraine, in Bucharest on April 4 and two days later in Sochi, Putin told president Bush that he apparently did not understand that ‘Ukraine is not a real state; ’that much of its territory had been ‘given away’ by Russia; that while western Ukraine belonged to Eastern Europe, eastern Ukraine is ‘ours’; and that, if Ukraine entered NATO, Russia would detach eastern Ukraine – in all likelihood he was also thinking of Crimea − and graft it onto Russia so that Ukraine would ‘cease to exist as a state’.

Yet other ‘practical steps’ taken by Putin to give substance to the assertion of special interests or − as then president Dmitry Medvedev called them after the Georgian war − ‘privileged interests’ on post-Soviet space have been the creation of the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) and measures adopted for the realization of the ‘Russian World’.

Eurasian Union

In an article published in the newspaper Izvestiya on 4 October 2011 Putin launched an initiative for the creation of a Eurasian Union to be based on the customs union of Russia, Belarus and Kazakhstan. Russia was ‘not going to stop’ at the planned removal of all barriers to trade, capital and labor movement in that organization but ‘we are setting an ambitious goal − to achieve an even higher level of integration’ and to set ‘a historic milestone for all three countries and for the broader post-Soviet space’ (italics mine). As the then absence of the term ‘Economic’ suggested, the project was to lead from economic integration to a political union.

In May 2014 the presidents of Belarus, Kazakhstan and Russia signed the Treaty on the Eurasian Economic Union. Photo Kremlin.ru

To that extent, it was modeled after the European Union, and explicitly so. As Putin explained, it had taken Europe 40 years to move from the European Coal and Steel Community to the full Union. In the east, however, that process could ‘proceed at a much faster pace’ because the countries concerned could ‘draw on the experience of the EU and avoid mistakes and unnecessary bureaucratic superstructures’. That this was the road that was to be taken was recognized and opposed by Belarus’ Alexander Lukashenko and Kazakhstan’s Nursultan Nazarbayev – one of the reasons why the ‘Economic’ was squeezed in between the ‘Political’ and the ‘Union’.

The project had an obvious geopolitical dimension. It was, among other things, designed to prevent the countries on post-Soviet space to sign and implement the EU’s Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreements (DCFTA). First and foremost, this concerned Ukraine. Severe pressure was brought to bear on the country in 2013. Medvedev, in his capacity as prime minister, told Kiev that it had to make up its mind: ‘You cannot sit on two chairs.’ Putin’s advisor on Eurasian affairs, Sergey Glazyev, warned Ukraine that it would be ‘suicidal’ to opt for the EU’s association agreement rather than the EEU.

When Ukrainian president Victor Yanukovich reneged on the commitment to sign the DCFTA at the Riga summit of the EU’s Eastern Partnership countries in November 2013, this set in motion the dramatic sequence of events leading from the Maidan revolution via Russia’s annexation of the Crimea to Moscow’s military intervention in support of the separatist republics of Luhansk and Donetsk. The net result, however, has been an upsurge of Ukrainian national consciousness and nationalism on an anti-Russian basis and the transformation of Ukraine from a friend and partner to an adversary.

Russian World

This, however, has done nothing to moderate Russia’s claims to the post-Soviet space as a Russian sphere of influence. In fact, in addition to the use of political, economic and military instruments, the Kremlin has increasingly resorted to the application of cultural and transnational societal means to foster its influence abroad. The concept underlying this approach has been that of the Russian World (Russkiy Mir). That world, as Putin explained in Izvestiya in January 2012, ‘unites all those who value the Russian language and culture, no matter where they live, be it in Russia or beyond its borders. The great mission of the Russians is to unite and bind together our civilization. Language, culture and “universal goodness” are, according to Fyodor Dostoyevsky, what brings Russian Armenians, Russian Azerbaijanis, Russian Germans and Russian Tatars together [and forms the basis for] establishing a civil society based on common culture and common values. This civilizational identity is based on the preservation of Russia's cultural dominance, which is not determined by the ethnic Russians, but by all those who feel committed to this identity regardless of their nationality.’

President Putin receives authors of new Russian history concept in 2014. Photo Kremlin.ru

President Putin receives authors of new Russian history concept in 2014. Photo Kremlin.ru

Institutionally, the Russian World is promoted by an organization bearing precisely this name, the Russkiy Mir foundation. The organization is lavishly financed through public and private funds and chaired by Vyacheslav Nikonov, a grandson of Soviet foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov. ‘After August 1991’, as its website blandly states, he was ‘a former assistant to the head of the State Security Committee (KGB) of the USSR’, that is, Vadim Bakatin. The organization’s website also states that geographically the Russian World encompasses ‘much more than the territory of the Russian Federation and the 143 million people living within its borders. Millions of ethnic Russians, native Russian speakers, their families and descendants scattered across the globe make up the largest diaspora population the world has ever known. Russkiy Mir reconnects the Russian diaspora with its homeland through cultural and social programs, exchanges and assistance in relocation.’

The concept of the Russian World puts in doubt the post-Soviet borders

Russian culture and language, as the Russian foreign minister has pointed out, ‘are not the only basis on which the contemporary concept of the Russian World is based. Another fundamental element is orthodoxy (pravoslavie).’ It is for this reason that the Russian Orthodox Church is used as yet another instrument for the assertion of Russian geopolitical interests. Lavrov has gratefully acknowledged this, saying that ‘The Patriarch of Moscow and All of Russia, Cyril, has supported the idea of the Russian World and several times has proclaimed the watchword of “Russia, Ukraine and Belarus - this is Holy Russia [Svyataya Rus’]”, as a part of which he also considered to be the Republic of Moldova.’.

The Russkiy Mir concept puts in doubt the borders between the nation-states that have been formed after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the promise of ‘protection’ extends to the large Russian minorities in Estonia and Latvia as well as in the northern part of Kazakhstan, and they are of particular importance in the actual and ‘frozen’ conflict areas on post-Soviet space, that is, Moldova’s Transnistria and the separatist entities of Luhansk and Donetsk in Ukraine but also in ethnically non-Russian Abkhazia and South Ossetia. In the Kremlin’s perspective, the Russian world also includes non-Slavic but Orthodox Christian Armenia and receives its support in its conflict with Azerbaijan over Nagorno-Karabakh.

Resurrecting Russia as a 'Great power'

It is unlikely that Putin used the term of ‘Greater Russia’, be it in the historical czarist versions of Velikaya Rossiya or Velikorossiya. Even if he did, it is doubtful that the associations conveyed by these terms have any specific present-day significance. His excursions into the czarist past have a merely instrumental significance. The frame of reference that is directly tied to his career is connected rather with the Soviet Union and with his idea that Russia is ‘just another word for it’.

It is patently obvious that there are deep personal and emotional aspects to his calling the collapse of the Soviet Union a major geopolitical disaster. He clearly has not reconciled himself with the loss of the Soviet Union’s superpower status, and he is therefore doing everything possible to resurrect Russia as a ‘Great Power’ (velikaya derzhava) on a par with the United States. Of course, the restoration of the USSR in its then existing legal and constitutional form is well-nigh impossible. What the Kremlin, however, appears to believe and is resolutely acting upon is the restoration of Moscow’s control over Soviet territory and the treatment of that space as an exclusive, special or ‘privileged’, sphere of influence.

The evident consequence of such attitudes has been the consistent attempt to counteract any close alignment of the ex-republics of the Soviet Union with NATO − a policy unsuccessful with regard to the Baltic States but successful in the cases of Ukraine and Georgia. It is not, however, only in military security terms that Moscow is drawing red lines but also in economic affairs, as evident in its opposition to the European Union’s association agreements and the Eastern Partnership − in Lavrov’s perspective an ‘attempt to extend the EU’s sphere of influence’ (italics mine).

There is no difference between the Yeltsin and the Putin era concerning the Kremlin’s claims and attitudes towards the post-Soviet space as an exclusively Russian sphere of influence. The difference rests in actual policies conducted to give substance to the pretensions. This is true for the military dimension, as evident in Russia’s ‘hybrid’ warfare for the annexation of the Crimea and the intervention in eastern Ukraine; for the economic dimension, as witnessed by the Eurasian Union initiative and the creation of the EEU; and, finally, the broad employment of ‘soft power’ instruments, as testified to by the large-scale propagandist efforts and the activities of the Russkiy Mir.

In sum, Putin’s attitudes concerning the collapse of the Soviet Union as being ‘catastrophic’ and ‘ahistorical’, his policies to restore ‘historical Russia’ and his efforts to create a ‘Russian World’ are squarely directed against the status quo. They have an entirely irredentist and revisionist character dangerous to peace and security in Europe. This does not mean, however, that we must now expect further military intervention on post-Soviet territory, notably in the Baltic States − as suggested by the large-scale Zapad (West) military exercises with the participation of Belarusian armed forces in September 2017.

Constant need for victories

Applying Max Weber’s typology of political systems, the Putin System can be classified as ‘charismatic’ and as such in need of constant legitimation through domestic and foreign policy victories. The annexation of Crimea was such a victory but one that may very well prove to have been exceptional. In eastern Ukraine, as the shelving of the Novorossiya project has demonstrated, costs and countervailing conditions have been in evidence. The Syrian intervention, sold as a success, has made little impression on the Russian public; the Kremlin is busily trying to understate its casualties, costs and risks. But any military incursion into the Baltic countries, members of the EU and NATO, would be incalculable adventurism to which Putin has never been prone. The military modernization, moves and maneuvers in the Baltic area, therefore, seem to be an indication of his view that the threat of military intervention may suffice to move the Baltic States to adopt policies advantageous to the Russian positions.