Navalny's death last Friday came as a shock, although it hardly surprised anyone. The unbearable conditions in which he was kept since January 2021 continuously pointed to a deliberate policy to let him rot in prison. Still, millions of Russians cherished the hope that Navalny would survive and lead them to a 'Beautiful Russia of the Future'. A deceptive mirage? Not quite, writes Associate Professor of Criminal Law at the University of Amsterdam Sergey Vasiliev. Placing Navalny's martyrdom in the context of Putin's ongoing persecution of political opponents, he argues that his death gives Russians the historical responsibility to make sure his sacrifice does not prove pointless.

Prison guards walk inside the prisoncolony in the town of Kharp (Photo: human rights ombudsman of the Yamalo-Nenets autonomous district)

Prison guards walk inside the prisoncolony in the town of Kharp (Photo: human rights ombudsman of the Yamalo-Nenets autonomous district)

By Sergey Vasiliev

For millions of Russians, 16 February 2024 became one of the darkest days in the already pitch-dark two years since Russia launched an all-out invasion of Ukraine, the bloodiest stage in the war the Putin regime started a decade ago. The news of the tragic death of Alexei Navalny (47) in the IK-3 (‘Polar Wolf’) jail in the village of Kharp first appeared on the webpage of the Directorate of the Federal Penitentiary Service (UFSIN) in the Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous District at 14:17 local time. It came as a shock, although it hardly surprised anyone.

The light’s gone out

A fierce and resourceful anti-corruption campaigner, Navalny was Putin’s arch-enemy and someone whose name the ageing dictator could not bring himself to utter. Navalny was not wrong to make the fight against corruption his main topic: corruption erodes the rule of law and democracy, opens doors to political violence and human rights abuses, and leads to autocracy which, lacking any effective internal or external restraints, turns its aggression outwards. For more than a decade, Navalny was the Putin regime’s staunchest and most effective critic. Putin despised, hated, and feared him — and hated him even more for that.

Neither flawless nor uncontroversial, Alexei was a true visionary and tremendously talented political organiser. He was an agile learner who adjusted quickly to perilous realities in Russia. He was always someone with ‘the plan’ – many plans. With his organic charm and charisma and an unparalleled ability to speak to everyone and bring everyone together, he was that ‘good, regular guy’ whom most Russians could understand and relate to. This explains Navalny’s personal popularity and unrivalled success of his grassroots organisation which he built up from scratch and which covered the whole of Russia – despite the persistent neglect and vilification by Putin’s officials and state media.

The younger generations of pro-democracy and anti-war Russians vested their hopes in Navalny, who awakened their political conscience and helped them believe in the imagery of the ‘Beautiful Russia of the Future’, a notion that he coined and embodied. Now it may feel as if the light of hope has gone out and this enticing vision of an alternative future has turned out to be a deceptive mirage. Not quite.

Murder and its cover-up

The strict-regime penal colony IK-3 is located in the permafrost zone some sixty km north of the Arctic Circle. It is infamous for having the harshest imaginable conditions of detention: a quintessential Gulag torture facility too remote to allow for minimal public control, let alone timely intervention. This is why Alexei was transferred there in December 2023 to serve the nineteen years’ sentence following his unjust conviction on the trumped-up charges of extremism. He was sent there to die. He did not last two months.

In January 2021, Navalny returned to Russia from Germany, where he convalesced from the August 2020 military-grade nerve-agent (Novichok) poisoning by the Federal Security Service (FSB) death squad. An attack that nearly killed him, and that Navalny himself famously helped investigate by prank-calling and extracting a confession from his poisoners. Navalny was arrested immediately upon landing in Moscow, after his plane was deviated to another airport to avoid the crowds of his supporters.

Navalny was never to live in freedom again. Over three hundred days of the three long years leading up to his death in Kharp, he spent in the punishment isolation cell (ШИЗО). He was placed there on twenty-seven occasions in total, under the pretext of ‘regime violations’. The pre-existing medical issues he had were exacerbated by the unbearably inhumane conditions of his detention and were never properly attended to, further undermining his frail health. The deliberate policy to let Navalny rot in prison was carried out with brutal methodism. Despite the still-valid moratorium on the death penalty in Russia, it was in essence a slow-motion execution.

The circumstances surrounding Navalny’s death have red flags all over them and scream ‘murder’

The direct cause of Navalny’s death is unknown and likely to remain so for very long if not forever. The circumstances surrounding it have red flags all over them and scream ‘murder’. First, the UFSIN notice contained atypical language and went up online two minutes after the ‘official time’ of Navalny’s death. This means that it was prepared in advance or that Navalny in fact died hours before.

Second, on 15 February Navalny participated in a hearing via video-link before the Kovrov court. Albeit emaciated, he appeared jovial and energetic – far from a man about to die. He even made the ‘prosecutor’ and the ‘judge’ (who are such in name only, considering their total lack of independence) smile at his signature ironic jokes. The cause of death put forth by state propaganda TV (RT) already on 16 February—a blood clot, or thromboembolism—was refuted the next day by the prison authorities when they pulled out another, just as implausible, version from their sleeve: the sudden arrhythmic death syndrome. All without an autopsy having been done. SADS is a rare condition—unlike the phenomenon of sudden death of anyone who had the temerity to cross Putin —and the statistical chance of Alexei succumbing to the former, rather than the latter, approaches zero. The truth is that it could rather be anything else: a knife or a shank, a brick, acute food or water poisoning, or a lethal injection administered surreptitiously in the back.

Third, the UFSIN notice stated that Alexei felt unwell during a walk and lost consciousness. Reanimation measures by the prison doctor and the ambulance team, which took seven minutes to reach the colony (plus two minutes to get through), were to no avail. But walks in the prison were typically scheduled at 6.30 am, not at 14.00. The distance between the closest town Labytnangi and IK-3 is thirty-five km. It could only be covered in seven minutes if the ambulance went at the speed of three hundred km/hour. In other words, it just does not add up.

Fourth, the Russian authorities said they had a medical examination conducted on the body—finding there was nothing ‘criminal’ about it (i.e. no bullet wounds)—and then another examination to try to establish the cause of death. Yet, they have refused to release the body of Navalny to his family and failed to disclose its whereabouts in the first two days, making Navalny’s mother and lawyer travel from Kharp to Salekhard in vain (another senseless and unthinkable cruelty). Having stated the need for an additional probe, the authorities may now legally wait for up to one month before handing the body over to the family. Whether they would be inclined to do so any time prior to the upcoming presidential ‘elections’ scheduled for 17 March, is doubtful. By the looks of it, a special cover-up operation to conceal the true cause of Alexei’s death is underway. The Investigation Committee of Russia cannot afford repeating past mistakes and leave room for an independent examination. Indeed, the risk is that impartial forensic experts might come to a conclusion that Navalny was helped to die.

But the direct cause of Navalny’s death does not matter fundamentally, because multiple indirect causes overdetermined it. The burden of justifying themselves rests squarely with the Kremlin, the prison system, and the Polar Wolf authorities. No one harbours any illusions about their willingness to conduct a credible inquiry and reveal the truth. Regardless of what a future autopsy might show, the death of Navalny must be laid at the doorstep of his jailers and their murderous thuggish boss, who attempted yet failed to kill Navalny with a chemical weapon at first but succeeded in destroying him in a torture facility only three and a half years later. As Alexei’s wife Yulia stated at the Munich Security Conference on the day of his death, Putin personally, his entourage and friends, and his government are and must be held accountable. The same holds for the ‘prosecutors’, ‘judges’, and UFSIN officers who maimed Navalny.

Flowers and messages left at the National Monument on Dam in Amsterdam after the death of Alexei Navalny (Photo: Wikimedia Commons).

Flowers and messages left at the National Monument on Dam in Amsterdam after the death of Alexei Navalny (Photo: Wikimedia Commons).

Political assassination

The crimes Navalny—and thousands of his past and present fellow inmates—fell victim to are not of the garden variety. They are the grave crimes under international law – murder, torture, persecution, and other inhumane acts as crimes against humanity. These crimes require the underlying acts to be committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack against a civilian population, with the knowledge of the attack. The Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC) defines such attack as a course of conduct involving the multiple commission of predicate offences pursuant to or in furtherance of a state policy. Although the ICC does not (yet) have jurisdiction over such crimes committed by Russian nationals in Russia, a state not party to the ICC Statute, the crimes against humanity were prosecuted in Nuremberg after WWII and are part and parcel of international law. The Russian Criminal Code tellingly does not contain a provision on the crimes against humanity, which can therefore not be prosecuted as such but only as ordinary domestic offences in Russia.

Nevertheless, this category of atrocity crimes captures best the Putin regime’s assault on its own population and characterises most accurately the ongoing political violence. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, in itself a crime of aggression, entailed a large-scale commission of war crimes and crimes against humanity in the occupied territories, for which accountability must and will follow. Nor can there be any doubt that, at least since 24 February 2022, a widespread and systematic attack against a civilian population within Russia has been underway, as the requisite context to the crimes against humanity, and that it is inextricably linked to Russia’s aggression and atrocities in Ukraine.

The Putin regime’s political repressions against his opponents and critics voicing opposition to the war amount to persecution as the crime against humanity. These victims and potentially others with a comparable civic position, whom Putin & co. refer to as ‘traitors’, ‘the fifth column’, ‘terrorists’ etc., are the members of an identifiable political group, just like many other persecuted collectivities

in Russia (for example, the LGBTQ+ community). The government, along with the co-opted and servile ‘prosecutors’ and ‘judges’, is intentionally and severely depriving the members of the group of their fundamental rights to life, liberty and security, fair trial, private and family life, and the freedom of expression. It does so contrary to international law and by reason of their political identity and belonging to that group – the textbook definition of political persecution. The persecution of the regime critics and antiwar activists is carried out under the draconian, totalitarian-style ‘laws’ on foreign agents, extremism, justification of terrorism, and disinformation about the army. This conduct has a clear connection with the war and related crimes in Ukraine and other crimes against humanity in Russia.

There are thousands of citizens languishing in Putin’s jails, who should not have spent a single day in there

The widespread and systematic character of the Putin regime’s attack against the civilian population is evident not least given the scale and severity of the political repressions. The most prominent political prisoners besides Navalny include politicians Ilya Yashin (eight years), Vladimir Kara-Murza (twenty-five years), Alexei Gorinov (seven years), Andrei Pivovarov (four years), Lilia Chanysheva (seven and a half years) and Boris Kagarlitsky (five years). Other high-profile cases are those of artists Evgenia Berkovich, Svetlana Petriichuk and Alexandra Skochilenko, journalists Ivan Safronov Jr., Alsu Kurmasheva, and Evan Gershkovich, and Navalny’s former lawyers Alexei Liptser, Vadim Kobzev, and Igor Sergunin. Yet, there are thousands of other lesser-known Russian (and a few foreign) citizens languishing in Putin’s jails, who should not have spent a single day in there. The grave danger many of them are facing should not be underestimated. It is as real as it gets, especially for those with public standing and/or links to Navalny personally or professionally.

Navalny himself was clearly a leading member of said persecuted group. On 24 February 2022, he unequivocally and forcefully condemned Russian aggression against Ukraine in his statement to the ‘court’: ‘I’m against this war. I believe that this war, which in fact is ongoing between Russia and Ukraine, was unleashed to cover up the robbery of the citizens, to take attention away from problems in this country. And this war will lead to an enormous number of victims on both sides, destroyed lives, and the continued impoverishment of Russian citizens… by that criminal gang which now holds power.’

There were many more anti-Putin and antiwar statements by him from prison in the next two years. He used nearly every mundane court hearing as an advocacy platform. The February 2022 invasion provided a post facto explanation of exactly why Putin had to get rid of Navalny by having him poisoned in August 2020. He saw Navalny as someone who had sufficient support and authority to mobilise mass protests that could seriously interfere with, if not derail, his plans for Russia, Ukraine, and beyond.

Fight not over

Alexei was not the first one in the long line of Putin’s critics to pay with his life for speaking out against human rights abuses and autocracy. The prominent journalist of Novaya Gazeta Anna Politkovskaya, murdered on 7 October 2006, Alexander Litvinenko, who succumbed to poisoning by polonium-210 in November 2006, and the high-profile politician and opposition leader Boris Nemtsov, gunned down nine years ago, are but some of the assassinated victims. Navalny surely knew that he could face the same fate when he weighed the prospect of leaving safety in Germany for Russia following his failed poisoning attempt. And yet, he decided to go back anyway.

Like most of us, he could not have foreseen that Putin would commence the full-scale war on Ukraine and that any form of dissent or opposition during wartime would be oppressed by Stalinist—or can those now safely be called Putinist? —methods. But Navalny was certainly aware of the grave risks to his life the decision to return would entail, having barely survived his encounter with Novichok. He was not at all naïve or overconfident. Rather, he was a true idealist and a patriot of his country, unlike his torturer. Some lament, especially after 16 February, that Navalny made a fatal mistake when he boarded the flight to Moscowto: a pointless sacrifice. Mind you, this was his carefully considered decision. Dismissing it as a mere miscalculation does not do it justice!

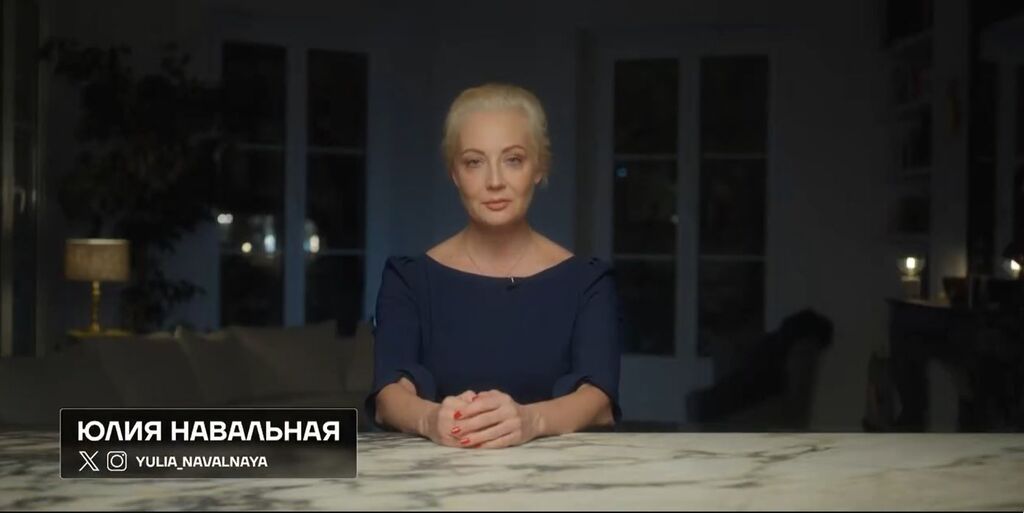

Yulia Navalnaya announces on February 19th that she will continue her husband's work (Photo: @yulia_navalnaya)

Yulia Navalnaya announces on February 19th that she will continue her husband's work (Photo: @yulia_navalnaya)

Fatal as it were, Navalny’s choice deserves utmost respect and admiration. A patriot in the real sense of the word, he felt he had to go back because he loved his country and was determined to fight for it. He believed he could not do that while staying abroad, as that was exactly what Putin hoped for. We must take the word for it. This level of courage is rare but not exclusive to Navalny. Vladimir Kara-Murza had been poisoned twice and still chose to return to Russia, where he is now serving a twenty-five years’ imprisonment. Ilya Yashin refused to leave Russia in full knowledge he would end up in jail for ‘spreading fakes’ about the army, i.e. for telling his compatriots about Bucha. This is pure self-sacrifice which very few are prepared to make. But such people do exist, and the last thing they deserve to hear from us is that their heroism is futile and wrong.

What makes Navalny’s death terribly tragic and painful, is how and where this contemporary yet already historical figure died. The larger-than-life, strong and progressive leader was ground down by the Gulag – like so many millions before him. There was hope even after his arrest that it might work out differently this time. He could survive, be freed, and go on to shape a different kind of politics in Russia. But nothing of this came to pass: the miracle did not happen.

This triggers the deeply seated trauma in the collective Russian psyche, which has never been properly processed and grew seriously aggravated over the past two years. Time and again, Russians prove unable to effectively resist and dismantle the cannibalistic machinery of the Gulag by themselves. There is and can be no place for Mandelas, Havels, and happy endings in the Gulag: it grinds everything and everybody to ashes, even the best and the strongest among us.

Navalny voluntarily walked into the jaws of the beast because he had faith in the people and in the ‘Beautiful Russia of the Future’

However, if there is anything to break the vicious spell of abandonment, lethargy and powerlessness, it is the martyrdom of Alexei Navalny. The idealist is no more, but the ideals he so doggedly and inspiringly believed in live on. Navalny’s life is the most powerful antidote to passivity and cynicism and his death offers the profound and paradigm-shifting symbolism which will retain its meaning far beyond present generations.

Like no one before him in modern Russian history, the smiling Navalny voluntarily walked into the jaws of the beast because he had faith in the people (‘we are a tremendous force!’) of the ‘Beautiful Russia of the Future’. His strength of conviction and faith in not just the possibility but inevitability of change, are both mind-boggling and infectious. Even though there is no one quite like him, new leaders are bound to appear (Watch Yulia…) and to continue his work.

Russians have failed to preserve Navalny. They bear a historical responsibility to see to it that his sacrifice does not prove pointless: He simply left them no other choice. This is why Putin(ism) is doomed.

The Polar Wolf has devoured Navalny but will choke on his corpse. The fight is not over.