In anger over the decision to grant the Ukrainian Orthodox Church independence from Moscow the Russian Orthodox Church broke off relations with Constantinople. This is good news for president Poroshenko, who wants to be re-elected next spring. The real challenge is to unite the three orthodox denominations in Ukraine into an independent national church. This, however, is unlikely to happen. And Moscow still owns most parishes in Ukraine. So it might be a purely symbolic victory, explains Andrii Fert on Open Democracy.

Patriarkh Filaret of Kyiv welcomes the news on the Tomos of Constaninople

Patriarkh Filaret of Kyiv welcomes the news on the Tomos of Constaninople

By Andrii Fert

The Ukrainian government has promised its citizens a new, independent Orthodox Church that will unite Ukrainian believers. But bringing several denominations together is harder than you think.

Over the last few months, the lexicon of many Ukrainians has been enriched by two new words: ‘Tomos’ (religious decree) and ‘autocephaly’ (religious autonomy). These words have been all over the media. In April this year, Ukraine’s president and parliament asked the Patriarch of Constantinople, the highest arbitrator in the Orthodox world, to recognise the canonical independence of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church. Religionhas dominated headlines and public debate ever since. For many, the Tomos is a kind of declaration of Ukrainian independence – not so much religious independence, but political.

Indeed, President Petro Poroshenko has stressed the political nature of this independence. Speaking on television recently, he declared that ‘this isn’t a religious matter. It isn’t simply a matter of state either. It’s a historic event, when Ukraine’s own church will return home after hundreds of years.’ Other public and political figures have echoed his sentiments. Vitaliy Deynega, a prominent activist on Ukraine’s frontline, posted this declaration on Facebook: ‘Many generations have fought for the independence of our country, including its spiritual independence… It’s important to free the hearts and minds of Ukrainian believers from the influence of [the Russian occupiers].’

But a closer look at the situation shows that it is less a matter of ‘freedom from influence’ or the unification of several denominations. Rather, this is about the creation of symbolic capital that will give Ukraine’s political elite an advantage ahead of next year’s elections.

The Ukrainian Orthodox Church under Moscow calls Poroshenko's initiative interference of politics in religious affairs. Metropolit Onufrii, the head of the church, even called the Tomos ‘a trap’. For the other two, however, the Tomos means legalisation at last by world Orthodoxy.

Three Ukrainian churches

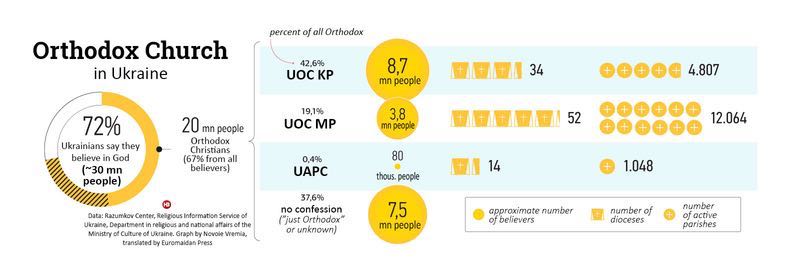

Ukraine has 3 Orthodox churches fighting for the role of ‘national church’. In numbers of dioceses and parishes the largest is the Ukrainian Orthodox Church, that after the breakup of the Soviet Union remained under the Moscow Patriarchate (UOC MP). After Ukrainian independance metropolit Filaret in 1992 declared the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Kyiv Patriarchate (UOC KP,) independant from Moscow, that excommunicated them. The Kyiv Patriarkhate was not recognised by Constantinople. The (small) Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church (UAOC) dates back to 1921, was supressed during communism and resurrected after the collaps of the USSR. In doctrines and liturgy all three are identical.

The Kyiv Patriarchate and Autocephalous Church want Ukrainian Orthodoxy to be independant from Russia, but the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate) sees Ukrainians, Russians and Belarusians as equal successors to medieval Kyivan Rus’, with a common faith and a common church.

Number of believers as divided over the three churches in Ukraine. Data: Razumkov Center. Graph by Novoie Vremia, translated by Euromaidan Press.

Number of believers as divided over the three churches in Ukraine. Data: Razumkov Center. Graph by Novoie Vremia, translated by Euromaidan Press.

Passers-by in church

‘What?’ a friend interrupts me during a conversation on the religious news, ‘is our Ukrainian church illegal, then?’ When I explan to her that the Kyiv Patrirachate is not recognised by the orthodox world community she is stunned. My friend, like many Ukrainians, goes to church once a year, at Easter, to have an Easter kulich cake and some eggs blessed. Her faith boils down to the observance of the unwritten commandment: ‘Thou shalt not work on church holidays’ and standing godmother to her friends’ children. Practising Orthodox worshippers call these people zakhozhane (church passers-by): they go to church now and then, light a candle for luck or have their kulich blessed, but take no active part in church life and don’t even know its basic teachings.

According to statistics, which some sociologists regard with suspicion, 67% of Ukrainians are Orthodox believers. But most of them are ‘semi-parishioners’. There are very few people who take their faith seriously – only 12% of Orthodox Church members.

There is yet another category of people. For them, being Orthodox doesn’t necessarily mean believing in God and going to church once a year. In 2017, Pew Research Center published a report on field studies of religious belief in Central and Eastern Europe (the former ‘Eastern bloc’, the USSR and Balkan states). The report found that ‘in these countries, national and religious identities have converged’ and that the church has become ‘one element of their national culture’. Respondents said, for example, that you have to be a Catholic to call yourself ‘truly Polish’ and Orthodox to be ‘truly Russian’.

For many Ukrainians Orthodoxy is an important part of their national identity

In Ukraine, 51% of respondents believed that ‘being Orthodox is very or somewhat important to truly be a national in their country.’ If you assume that 12% of practising Orthodox believers, divided between three denominations, are part of that number, there is still an enormous number of people for whom Orthodoxy is an important part of their national identity.

But let’s add some context here. In 2014, Russia annexed Crimea and is now at war with Ukraine via its puppet regimes in Donetsk and Luhansk. Meanwhile, Ukraine’s largest church [in amount of parishes and churches] is still subordinated to the Moscow Patriarchate. How does that look to people for whom Orthodoxy is first and foremost an important part of the Ukrainian national project and who don’t pay a lot of attention to doctrine or church rules? Obviously, it is an unhealthy contradiction that needs sorting out. ‘Soon there will be one unified national church,’ says Crimean Tatar journalist Aider Mudzhabayev in his videoblog, ‘I see this as a big step forward. God willing….hmmm, I’m an atheist, but God willing it’ll go that way.’

For many ‘church passers-by’ and atheists like Mudzhabayev, ‘our’ ‘Ukrainian’ church should be recognised and receive a Tomos on autocephaly.

Victims and colonisers

These two groups and this mindset are the main targets of the Ukrainian elite. ‘A Ukrainian church for the Ukrainian state’ is the slogan of a Facebook group created by civic leaders, theologians and clergy. Experts and politicians repeat the debate on social media. An independent Ukrainian Church is ‘the last missing piece to make Ukraine truly independent’, wrote the Atlantic Council. ‘A national autocephalous Ukrainian Orthodox Church is a key element in our statehood and independence,’ Poroshenko told viewers on live TV.

The world famous Kyiv Pecherskaya Lavra is the see of the Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate. It is a famous destination for pilgrims. Kyiv would like to have it back.

The world famous Kyiv Pecherskaya Lavra is the see of the Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate. It is a famous destination for pilgrims. Kyiv would like to have it back.

All these statements are part of the same principle – a connection between nation building and an independent church. And there are several important factors here.

The first is the politics of memory. From the start of the war in eastern Ukraine in 2014, the politics of memory has been centred on demonstrating the age-long struggle between Ukrainians (victims) and Russians (colonisers/enslavers), as well as emphasising successful instances when the ‘Ukrainians’ fought/beat the ‘Russians’.

In the politics of memory autocephaly is an important victory over the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union

According to this logic, autocephaly is an important and essential victory over the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union, of which Ukraine was long part. According to the social media campaign, this empire ‘unlawfully seized the Ukrainian Church after the annexation of the historic Left Bank Ukraine in the 17th century’ and appropriated its history. This empire has, much in the same way, appropriated the history of Ukraine itself, from the 11th century princess Anne of Kyiv, the daughter of Kyiv Duke Yaroslav the Wise, to the whole of the ‘Ukrainian’ middle ages.

Thousands of believers who belong to the Moscow Patriarchate hold processions in Kyiv every year

Thousands of believers who belong to the Moscow Patriarchate hold processions in Kyiv every year

Once the Ukrainian Church becomes independent, the ‘imperial’ or ‘colonial’ historical narrative will finally be overcome. ‘The story of the Russian Church will begin not with Kyivan Rus’ in the late ninth century but with 1448, the point at which it split from the Kyiv Metropolitanate,’ says Filaret, head of the Kyiv Patriarchate. ‘Ukraine was never, is not and never will be part of Russia. Rus’ existed, but Russia as an entity didn’t. And when it appeared, it was called Muscovy, while Rus’ was present-day Ukraine. And even Crimea is Ukrainian, because it belonged to Rus’.’

Autocephaly is also seen by Ukraine’s political elite as a tool for encouraging patriotism, essential for protecting the country from external aggressors. The New Church will be a patriotic church that knows who is fighting whom in the east Ukraine, and which supports the armed forces against the self-proclaimed ‘Luhansk People’s Republic’ and ‘Donetsk People’s Republic’. And this is why the Tomos is so important – a church that encourages Ukrainian patriotism can’t be unlawful. As Petro Poroshenko never tires of repeating: ‘The army protects our Ukrainian lands, our language protects our Ukrainian hearts and our faith protects our Ukrainian soul.’

This is why the issue of autocephaly is a litmus test to define who ‘we’ and ‘they’ are. ‘Whatever you think about Poroshenko or the political parties, autocephaly is a good thing. There can be no argument with that,’ says Aidar Mudzhabayev.

Uniting the churchgoers

There’s one intriguing question left here: where are the practising Orthodox churchgoers who are to go to this ‘United National Orthodox Ukrainian Church’? How will the long-expected Tomos affect those who go each Sunday to churches of various hues and bring their own ideas of ‘obedience’ with them?

The well-known theologian Ciril Hovorun, a former employee of the Department for External Church Relations of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church who now teaches at a number of Western universities, recently told an audience at a public lecture in Kyiv: ‘The main thing for the politicians it getting the piece of paper – the Tomos of autocephaly – but they haven’t thought about what they’re going to do next, how they are going to create a new church.’

This new church, as imagined by President Poroshenko, will act as a unifying force for Ukrainian believers and will stem the anti-Ukrainian propaganda being spread among churchgoers by the Moscow Patriarchate. But for that to happen, all three denominations, each with their own followers, will have to amalgamate.

But the denomination with the largest number of practising churchgoers – the Ukrainian Orthodox Church which is subordinate to Moscow – has already refused to take part in the creation of this new church. So that just leaves the Kyiv Patriarchate and the Ukrainian Autocephalic Orthodox Church. ‘If all goes well, we shall amalgamate,’ says the head of the latter, Metropolitan Makarii. ‘And those who refuse to unite with us will have to call themselves the Russian Orthodox Church in Ukraine,’ Kyiv’s Patriarch Filaret declares confidently.

Obviously, this will mean big changes for practising Kyiv Patriarchate and Autocephalous Church members. The Orthodox world officially recognises their churches as bodies that save souls and have the grace of God. But Ukrainian Orthodox Church congregations will probably be forced to rename themselves into ‘Russian Church in Ukraine’. And their integration will be a crucial issue when creating a real united Church.

‘Why do we need to think about integrating with these Moscowdox types anyway?’ asks one of my Facebook friends. And it’s true that there are very few of them – polls show that only 13% of Ukrainians regard themselves as belonging to the Moscow Patriarchate, as opposed to 29% who belong to the Kviv Patriarchate. But these figures don’t actually reflect the numbers of practising members of one denomination or the other. The Kyiv Patriarchate’s 29% includes the ‘church passers-by’ and patriotically-minded groups for whom it’s important to belong to that church ‘if you want truly to be a national of Ukraine.’

Russian Church in Ukraine

After the Tomos is received, the ‘Russian Church in Ukraine’ will have more congregations and monasteries than the potentially united National Church (about 12,000 congregations and 200 monasteries as opposed to 5,000 and 60). But there’s no need to panic: about 30% of them will transfer to the new church as soon as the Tomos arrives, says Tetiana Derkach, a religious commentator. ‘The war in the east and the hybrid role played in it by the Russian Orthodox Church has alienated many former Moscow Patriarchate churchgoers, who have now turned to the ‘domestic market’ and taken the extreme step of refusing to pray for the (Moscow) Patriarch Kirill.

And, as though to confirm Derkach’s words, priest of Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate) Father Heorhii Kovalenko has made a statement, saying that, ‘we, the clergy and parishioners of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (MP) have begun a dialogue on what the Orthodox Church of Ukraine should be and its place in society. Most of us are convinced and stalwart supporters of autocephaly.’ This statement has been open for signatures on Facebook and, as of 27 August has collected over 20 signatures of Ukrainian Orthodox clergy and several dozen lay members of the church.

Filaret visiting Ukrainian troops in the Donbass

Filaret visiting Ukrainian troops in the Donbass

But this initiative is little more than a drop in the ocean – nothing like the alleged 30%. Nikolay Mitrokhin, a leading specialist on the contemporary Russian Orthodox Church, recently conducted a field study of churches in Ukraine. He writes that ‘realistically, only the group around (Ukrainian Orthodox Church) Metropolitan Aleksandr Drabinko, as well as five well-known Kyiv priests and a maximum of 50-60 priests from other regions of Ukraine are ready to take part in the united autocephalic project.’

‘The core of believers who take part in all the prayers take their lead from the monastic abbots. And if the abbots say that they don’t want anything to do with this, then their parishioners won’t accept it either,’ Mitrokhin concludes. ‘In other words, the generals and officers, as it were – that is, the bishops and priests – will happily transfer their loyalties, but this force will be useless without its ordinary rank and file parishioners.’

For many to tear apart the spiritual unity of ‘Holy Rus’ (Ukraine, Russia and Belarus) is close to a sin

The potential integration of these believers is complicated by two more issues. The first is the internal contradiction in the very idea of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church – the attempt to simultaneously retain both their loyalty to Ukraine and their submission to the Moscow Patriarchate. The self identification of this denomination’s parishioners and clergy is based on the idea of the spiritual unity of ‘Holy Rus’ (Ukraine, Russia and Belarus), and to tear that apart would be close to a sin.

The second issue is the public’s attitude to practising believers of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Moscow branch. Most of the media regard the members of this denomination as something out-of-date, a fifth column, accomplices of Moscow, and accuse them of a lack of patriotism. These non-patriots from the ‘Moscow church’ can then be contrasted with the genuine patriots of the Kyiv Patriarchate.

Symbolic victory

Ukrainian society, which has been dragged into a war with Russia, has a desire to have its own Orthodox Church, independent of Russia. So it’s no surprise that the president and the political elite are taking advantage of the Tomos issue. If, after all, Ukraine receives this magic piece of paper, this can be converted into votes at the elections.

At the same time, it’s important to realise that the Tomos request has less to do with practising believers than with ‘church passers-by’ and other people for whom the church is first and foremost an important part of their Ukrainian national identity. This is why there is a lack of interest in what will happen after the Tomos arrives, how a new church structure will be created and how members of the various denominations will be integrated in it. The main thing, after all, is to create a symbol: an Independent United National Ukrainian Church – patriotic and recognised by Orthodoxy around the world.

In the circumstances, however, this united church is very unlikely to be genuinely united. Practising believers, who mostly belong to the Moscow Patriarchate, will not join it. This will be for various reasons: their conservatism, their conception of the unity of the Russian Church and their reputation in the eyes of the public. In this sense, the united national church – if it receives its Tomos – will be merely a symbolic victory for Ukraine’s patriotic ‘church passers-by’.