Patriotic history exhibits, unashamedly nationalist videos, pyrotechnic military Olympics: the Kremlin is turning to Russian creativity as a tool of domestic mobilisation and geopolitical outreach. And with a mix of wit, glitz and irony, our columnist Mark Galeotti thinks it is doing it rather well, even at a time when the overall national mood is sombre.

Minister of Defense Shoigu (left) at the International Army Games 2018 (picture Russian Ministry of Defense)

Minister of Defense Shoigu (left) at the International Army Games 2018 (picture Russian Ministry of Defense)

The surprise foreigners expressed when encountering Russia during this summer’s World Cup – it’s so modern, the streets are safe, the trains run well, there are nice places to eat! – in part reflect the enduring stranglehold on the popular imaginary of tropes of the past. From the drab dourness of the late Soviet era to the frenzied anarchy of the 1990s, these malign and outdated clichés completely fail to grasp today’s Russia. This is a political challenge, too, as public, pundits and policy-makers alike too often respond to a Russia that maybe never was, but certainly isn’t now, rather than the present reality.

One particular failing, especially often encountered in the United States, is for the widespread belief that Russia is still somehow ‘communist’ (regardless of whether that label could ever be applied to the Soviet model). From the hackneyed use of scary red banners and hammers and sickles, to more subtle assumptions about Russians’ supposed collective habits and lack of entrepreneurial flair, this crops up time and again.

Of course, that is ridiculously, dangerously far from the reality. If anything, Russians are amongst the most flexible, imaginative and, yes, rapacious of capitalists, not least because most Soviet citizens were essentially taught to buy, sell, deal, and haggle on every occasion by a lumbering, inadequate and deeply unequal command economy. Ironically, much of Russia’s economy, with its eager seizure on the latest fad, light touch regulation and inadequate consumer, environmental and worker protections, would be every neo-con fat-cat entrepreneur’s dream, were there also rule of law.

Kremlin creativity

Likewise, I have been struck by a failure by many to appreciate how creative Russians can be, and that this is a creativity not confined to the opposition or even the troll farms. The 2014 Sochi Winter Olympics and this year’s World Cup showed that the Russians know how to put on a show. From the security to the pageantry, the latter was especially impressive in a time of heightened geopolitical tension, and it can only be considered a soft power triumph. Of course, as I’ve already said, this new capital could so easily be squandered.

However, in many other ways the Russians are demonstrating a trademark combination of wit, glitz and irony. For all the one-sided propaganda of much of its output, the TV channel RT has long been regarded as a technically slick and effective outfit, easily up to the standards of its global rivals. But beyond that, it is striking how hip even the most objectional messages can be made.

In 2015, for example, the controversial video ‘I am a Russian occupier’ went viral, with its mix of fancy graphics and uncompromising defence of a vision of Russian and Soviet imperialism that developed and enriched those nations it conquered. 'Yes, I’m an occupant!', it concluded, 'and I’m tired of apologizing for it!' The brainchild of one Evgeny Zhurov, it epitomised a particular theme in the new expression of a new nationalism, an appropriation and subversion not just of Western idiom but also of the very critiques levelled against Russia. Whereas once the focus would have been on rejecting the accusation of being an imperialist and an occupier, now it is about embracing it, and seeking to give it a new meaning.

This is a powerful message for both domestic and some international audiences. As Russia grapples with its sense of itself after the collapse of the Soviet Union, no longer a great power and yet still a multinational state, there is a powerful desire to feel good about themselves. Perhaps best illustrated by the depressingly widespread urge to whitewash Stalin, or at least pass over his murderous crimes as a mere detail of history, this is not something confined to Communist Party relics or an ill-educated lumpenproletariat.

A Russian put it to me that 'we’re tired of being apologetic about our past, tired of being told what to do and how to be'. This is precisely the sentiment to which Putin is able to appeal, a belief – dramatically exaggerated, but not wholly fanciful – that Russia has been treated badly and that it is having to assert its national rights against a hostile and hypocritical West.

Nationalist spectacle

And this lends itself to spectacle. There are the toxic panel discussions and talk shows on TV, where a series of talking heads try to outdo themselves in choleric critique of the West and its decadent values, while hoping their visas for a family holiday at Eurodisney will come through. There is the overt creation of a national historical narrative in which disunity means vulnerability in a hostile and opportunistic world, and in which Russia’s story is one of escalating triumphs, won through common purpose and strong leadership. The Rossiya – moya istoriya (‘Russia – my history’) exhibit, first opened in Moscow and then rolled out across the country, is a perfect example, a multimedia pageant that steamrolls over nuance and instead blazes a triumphalist path through a thousand years of history.

Military power, still one of the areas in which Russians can feel truly like a world power, is thus not just a celebration of soldiers past and present but also of how all of society should feel connected with the military.

Exhibition 'Russia - my history' in Moscow's Parc of People's Achievements

Exhibition 'Russia - my history' in Moscow's Parc of People's Achievements

From the International Army Games, military exercises pitched as televised sporting event, and underscoring that while the West is levying sanctions on Russia, 31 other countries, including China and India, are happy to come play, through to the raucous shows on the defence ministry’s own Zvezda TV channel, might and message are one and the same.

This epitomises the new face of the Kremlin’s nationalism. It presents the military – and by extension their brooding master, the commander in the chief – as vital protectors of state and society in a dangerous world in which the West is somehow at once pitifully decadent and also ruthlessly hostile. It seeks to make the military a metaphor for the nation, making everyone think of themselves as having some role to play in the service of the state. (I cannot help but wonder how long before some parliamentarian suggests returning to the tsarist-era practice of uniforms for all.) But it also seeks to appropriate the liberal and Western critique, with an ironic wink. Call us aggressors, oppressors, occupiers? Well, if so, at least we can be hip, smart, dangerous ones. At least we can be proud of how good we are at it.

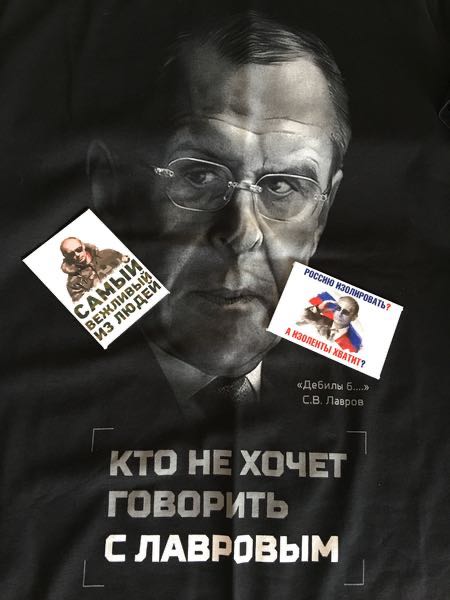

In many ways this inverse pride was best captured by a t-shirt I saw last week at an Army Store in Moscow. 'Whoever doesn’t want to speak to [foreign minister] Lavrov', it warned, 'will have to speak to [defence minister] Shoigu'. And they were almost sold out of them.

T-shirt: 'Who doesn't want to talk with Lavrov, has to talk to Shoigu'

T-shirt: 'Who doesn't want to talk with Lavrov, has to talk to Shoigu'