Many statements of Donald Trump may be contradictory, his plan to 'rebuild the US military into the strongest on earth' has been consistently expressed. Putin's Russia aims to rise again to the status of a Great Power, with ‘greatness’ understood primarily in military terms. Modernization of its arsenal, integration of conventional and nuclear weapons and the dangerous notion that nuclear war is a possibility are part of Russia's strategy. According to military expert Hannes Adomeit both countries embark upon an irrational and costly arms race.

Nuclear weapons have been one of Russia’s most important status symbols and instruments for the exercise of influence abroad. In conjunction with the vast geographical extent of the country, the relatively high educational level of its – in European comparison – numerous population, and its rank as a permanent member of the UN Security Council, they have served as the basis for the claim of being a truly Great Power (velikaya derzhava) ‘at eye level’ and ‘on equal footing’ with the United States.

In the world, there are an estimated 14,900 nuclear weapons, with the United States and Russia accounting for 93 percent of them. Their respective shares are almost evenly divided between them, 6,800 for the US and 7,000 for Russia.

Like its Soviet predecessor, today’s power elite in Moscow is obsessed with the maintenance of actual or perceived ‘strategic parity’ with the United States, reacting with irritation and hurt pride to mere suggestions, like that by former US president Barack Obama, that Russia may just be a ‘regional power’. In comparison to the Cold War, however, the Kremlin has changed its terminology. No longer portraying global politics as ‘bipolar’ but as ‘multipolar’, it doesn't aim at ‘parity’ anymore, but is maintaining a ‘global strategic balance’ or ‘global strategic stability’, as if taking into consideration the interests of the remaining nuclear powers.

Balance under threat

Objectively, balance and stability Russian style are under threat. Donald J. Trump, the 45th president of the United States, wants ‘to make America great again’. Like his Russian counterpart, he defines greatness first and foremost in military ‘hard power’ terms, and that, of course, includes strategic nuclear weapons. No matter how vague and contradictory many of his statements may be, Trump has consistently claimed that the Obama administration allowed US military power to wane and that this was one of the reasons why US influence abroad has decreased. As a result, in conjunction with Obama’s (alleged) lack of leadership qualities, nobody takes America seriously any more.

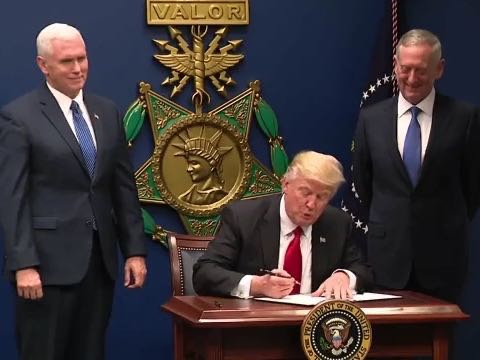

Trump pledges to 'make America great again'. Photo Wikimedia

Trump pledges to 'make America great again'. Photo Wikimedia

All of this has to change. Accordingly, the platform of the Republican Party for the 2016 elections, as approved by Trump, states that the party ‘is committed to rebuilding the U.S. military into the strongest on earth, with vast superiority over any other nation or group of nations in the world’. He himself later deplored that the ‘Russians and Chinese have rapidly expanded their military capability’ and asserted: ‘Our military dominance must be unquestioned’. The United States, he demanded, ‘must greatly strengthen and expand its nuclear capability until such time as the world comes to its senses regarding nukes’. In another statement he mused that ‘it would be wonderful, a dream would be that no country would have nukes’, but added that ‘if countries are going to have nukes, we're going to be at the top of the pack’.

Trump’s claim of US ‘weakness’ as a result of the dismantling of the country’s military capabilities under Obama is evidently wide of the mark. It is also difficult to see how ‘superiority’ or ‘dominance’ in the strategic nuclear competition can be measured and, even more importantly, what could be the political advantages to be derived from such a state of affairs. There is one aspect, however, where Trump has a point. In relative terms, Putin’s Russia has paid far more attention to nuclear weapons issues than the United States. That applies to modernization programs for offensive strategic weapons, military doctrine governing the employment of nuclear weapons, simulation of their use in military maneuvers, and using them as an instrument in support of foreign policy.

Russia modernizes its strategic forces

Russia has made particular efforts to modernize its land-based and sea-based strategic delivery systems capable of delivering hundreds of warheads against the United States. The mainstay of its deterrent continues to be the land-based ICBMs (intercontinental ballistic missiles) of the Strategic Missile Forces (RVSN), a separate branch of the Russia's Armed Forces, subordinated directly to the General Staff. In 2016 Russia tested yet another missile, the RS-28 Sarmat, a hundred-ton, twelve-warhead giant that makes America’s thirty-nine-ton Minuteman ICBM look like a dwarf.

Its new component is the Borei-class, nuclear-powered submarine. A total of eight Borei-class submarines carrying 148 missiles, each with a nuclear warhead of 100-150 kilotons, are to be built and to be operational by 2020.

The third part of the strategic nuclear triad is Russia’s long-range bomber fleet. Its size is but a fraction of what it used to be in the Soviet era. However, its modern component is its armament, the Kh-101 and Kh-102 long-range cruise missiles with stealth and precision-strike capability. The range of the missiles, estimated to be as vast as 3,100 miles, makes it unnecessary to penetrate enemy airspace.

Russia also has stubbornly clung to a large and varied arsenal of shorter-range, ‘tactical’ or ‘non-strategic’, nuclear weapons (NSNW). At present, its size is estimated to amount to 2,000 warheads. Perhaps more than anything else, the existence of these weapons underlines the fact that the Kremlin puts a high premium on its nuclear capabilities.

For details about the nuclear force press the + button

{slider Volledige tekst|closed|icon}

Russia possesses 299 operational missile systems of five different types that can carry a total of 902 warheads. The main force consists of 76 1970s vintage R-36M2 (NATO designation: SS-18) and UR-100NUTTH (SS-19) missiles as well as 150 Topol (SS 25) and Topol-M (SS-27) missiles (essentially the equivalent of the US Minuteman III) in both silo-based and mobile versions. In 2015-2016, the RVSN acquired twenty-seven new RS-24 Yars units (SS-27 Mod 2), also deployed in silo's and mobile; these are missiles that can carry up to three or four MIRVs (independently targetable warheads) and are capable of penetrating missile-defense systems.

Giant nuclear weapons

In 2016 Russia tested yet another missile, the RS-28 Sarmat, a hundred-ton, twelve-warhead giant that makes America’s thirty-nine-ton Minuteman ICBM look like a dwarf. This is presumably one of the systems to which Putin referred when he said that Russia was paying close attention to the development of ‘weapons based on new physical principles’ that have ‘selective, pinpoint impact on critical elements of armaments, equipment, and infrastructure of a potential enemy’. The missile will have the ability to place the warhead in a suborbital trajectory and strike from literally anywhere on the globe.

The warheads will enter the atmosphere at hypersonic speed and move along a larger trajectory, maneuvering at a speed of 7 to 7.5 kilometers per second. Eventually, it is thought, the RS-28 will constitute 100 percent of Russia’s ICBM force.

The second and in future the main part of Russia’s strategic nuclear triad is its sea-based deterrent. It, too, is undergoing rapid and expensive modernization.

Borei-M submarine 'Vladimir Monomakh', almost ready for launching. Photo Russian Ministry of Defence

Borei-M submarine 'Vladimir Monomakh', almost ready for launching. Photo Russian Ministry of Defence

Its new component is the Borei-class, nuclear-powered submarine. Its most modern version, the Borei-M, has a length of nearly 170 meters, a width of 13.5 meters, and a displacement of 24,000 tons. It can carry 16-20 Bulava-30 intercontinental ballistic missiles and several cruise missiles with a maximum range of 8,000 km. It has eight 533-mm forward torpedo tubes, up to 40 torpedoes, missile-torpedoes and torpedo mines, carries autonomous sonar countermeasures devices, can override advanced missile defense systems, has increased stealth capabilities, and possesses advanced communications and weapons control systems. A total of eight Borei-class submarines carrying 148 R-30 Bulava missiles, each with a nuclear warhead of 100-150 kilotons, are to be built and to be operational by 2020.

Debut strike in Syria

The third part of the strategic nuclear triad is Russia’s long-range bomber fleet. Its size is but a fraction of what it used to be in the Soviet era. The force is based on 63 Tu-95MS (NATO-designation: Bear) of which perhaps 55 are operational. It is the Russian long-range air force’s ‘workhorse’, in service since 1956. The other strategic bomber is the Tu-160 (Blackjack) which entered service in 1987. Russia has 16 original model Tu-160 airframes, of which perhaps half are available for operational missions. The bomber force is far from impressive both in terms of its size and modernity.

However, its modern component is its armament, the Kh-101 and Kh-102 long-range cruise missiles with stealth and precision-strike capability. The range of the missiles, estimated to be as vast as 3,100 miles, makes it unnecessary to penetrate enemy airspace. The bombers would be able to move into position to launch cruise missiles from stand-off distances. The new weapon Kh-101 with a conventional warhead made its debut in November 2015 from a Tu-160 with strikes against targets in Syria.

Russia launches cruise missiles against targets in Syria from a ship in the Caspian Sea. Video Russian Ministry of Defence

Russia also has stubbornly clung to a large and varied arsenal of shorter-range, ‘tactical’ or ‘non-strategic’, nuclear weapons (NSNW). At present, its size is estimated to amount to 2,000 warheads. The armed forces’ capabilities include about 500 tactical nuclear air-launched missiles and aerial bombs for 120 medium Tu-22M bombers and 400 front-line Su-24 bombers. Perhaps more than anything else, the existence of NSNW underlines the fact that the Kremlin puts a high premium on its nuclear capabilities.

{/sliders}

Lowering nuclear threshold

This feeds suspicions that Moscow is lowering the threshold for the use of nuclear weapons and is developing new low-yield nuclear warheads. It also confirms basic precepts of Russian military doctrine. Unlike the Soviet Union, which had adopted a ‘no first use’ policy, the new Russian Federation explicitly rejected that commitment as early as in its 1993 military doctrine. In fact, as Moscow’s conventional forces continued to decay during the economic and social meltdown of the 1990s, Russia adopted the position that if the country were faced with the defeat of its conventional forces, it might resort to nuclear weapons. The latest version of the military doctrine of 2014 confirms that revision. It states that Russia will use nuclear weapons in situations ‘that endanger the very existence of the state’.

Putin’s realization of the use of weapons, whether conventional or nuclear, in support of Russian foreign policy was most clearly expressed in his commentary about the employment of long-range, conventionally armed cruise missiles from surface ships in the Caspian Sea against targets in Syria in October 2015.

‘It is one thing,’ he said on Russian national television, ‘for the experts to be aware that Russia supposedly has these weapons, and another thing for them to see for the first time that they do really exist, that our defence industry is making them, that they are of high quality and that we have well-trained people who can put them to effective use. They have seen, too, now that Russia is ready to use them if this is in the interests of our country and our people.’

Putin's landmark speech in Munich, 2007. Photo Kremlin

Putin's landmark speech in Munich, 2007. Photo Kremlin

The Kremlin’s use of its nuclear arsenal in support of foreign policy interests came in August 2007, half a year after Putin’s memorable speech at the Munich international security conference and in conditions of severely strained US-Russian relations. Putin announced that the Russian Air Force would resume regular, long-range patrols by nuclear-capable bombers over the world’s oceans, renewing the practice after a 15-year hiatus. The patrols would not be part of routine exercises but form a permanent feature of the Russian strategic posture.

They would, as Putin said explicitly, continue ‘from this day on’. The patrols included Tu-95 and Tu-160 airplanes. According to the Russian defence ministry, they were part of a fleet of 79 strategic aircraft, capable of carrying 900 nuclear-armed cruise missiles. The conclusion that could be drawn from the resumption of long-range patrols was evidently that Russia considered the Cold War military-political confrontation with the United States and NATO either never to have ended or to have been restarted.

Iskander deployed or not?

Another example of Soviet-style use of weapons as a political instrument is the Iskander-M (SS-26). This is a ballistic missile of high precision with a range of 400 to 500 kilometers that can be equipped with conventional or nuclear warheads. It carries a maneuverable re-entry vehicle (MaRV) and decoys to defeat theater missile defense systems. The Iskander-M was first used in combat during the Russo-Georgian war in August 2008 by the Russian Army to strike targets in Gori.

Exercise with ballistic missile Iskander-M. Photo Russian Ministry of Defence

Exercise with ballistic missile Iskander-M. Photo Russian Ministry of Defence

Moscow has put the weapon squarely into the context of the alleged necessity to counter US and NATO efforts for the construction of an anti-missile defense system in Europe, which Russia has (absurdly) called a threat to its land-based ICBM strategic deterrent. Correspondingly, on 5 November 2008 then president Dmitri Medvedev stated unequivocally that ‘we will deploy the Iskander missile system in the Kaliningrad region to be able, if necessary, to neutralise the missile defence system’. Implementation of the move, that is, transfer of the missiles to the 152nd Independent Missile Brigade stationed outside Chernyakhovsk in the Kaliningrad oblast, was suspended eighteen months later, in response to the once-planned and then deferred U.S. deployment of ballistic missile defence (BMD) systems in Poland and the Czech Republic.

The stationing threat, however, resurfaced sporadically. Thus, in December 2014 and March 2015, Iskander-M missiles were reported to have been deployed during so-called ‘snap’ − meaning without prior notification to the West − military drills in Kaliningrad but it remained unclear whether the transfer was temporary or permanent. Even today, it is uncertain whether the stationing of the missiles and their protection with the modern S-400 anti- aircraft defence systems, which has been ‘confirmed’ several times by both Russian and Western sources, are a reality. It seems that the Kremlin likes to keep the Iskander-M deployment threat alive there (as well as in Crimea) as a device that can be brought up at its convenience.

Although the Iskander-M can be equipped with both conventional and nuclear weapons, the latter are the club that is raised for purposes of threat by Moscow. This is true not just vis-à-vis the NATO countries adjacent to the Baltic Sea but also in relation to NATO members bordering the Black sea. Thus, in December 2014 Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov claimed that Crimea was never a ‘nuclear-free zone’ even though Ukraine had given up its atomic weapons by treaty. ‘Now Crimea has become part of a government that has such weapons in accordance with the non-proliferation treaty, and the Russian government has, in accordance with international law, every right to deploy its legitimate nuclear arsenal according to its interests.’

Nuclear option - a possibility?

As part of its threat posture, Russia has deliberately created the perception that nuclear war in Europe is again thinkable. Its exercises demonstrate that the Russian armed forces are increasingly ready to conduct different kinds of nuclear operation and that their nuclear and conventional capabilities are closely intertwined. Thus, NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg in his 2015 annual report claimed that Russia’s air force, using Tu-22М3 Backfire long-range supersonic bombers under cover of Su-27 fighters, had conducted a training mission two years earlier that was actually a ‘simulated nuclear attack’ on Sweden.

The Ukraine crisis was accompanied by an unprecedented number of nuclear signals from the Kremlin. During the height of the Ukrainian crisis (summarized by military analyst Jacek Durkalec), Russian politicians including the president repeatedly issued implicit and explicit nuclear threats directed at NATO. Thus, in August 2014, Putin warned NATO not to ‘mess with nuclear-armed Russia’, and in October 2014, he praised Nikita Khrushchev’s nuclear brinkmanship, which in his view convinced the United States and NATO that ‘Nikita is best left alone’.

In March 2015, Putin publicly stated that he was ready to put Russia’s nuclear weapons on alert during the annexation of Crimea. Moscow stepped up its nuclear bomber diplomacy, carrying out more offensive patrols near the airspace of NATO allies and partners. It increased their number, scale, and range, and conducted more provocative mock nuclear attacks, including against the US in September 2014. Russia also − in March 2014, May 2014 and February 2015 − conducted a series of military exercises, including ‘snap’ drills and command post exercises to test the delivery systems of strategic and non-strategic nuclear weapons.

Irrational

‘If you go on with this nuclear arms race, all you are going to do is make the rubble bounce,’ Winston Churchill stated wryly in 1952. That was at a time when the nuclear age was in its infancy − just three years after Russia tested its first nuclear bomb, and five years before the United States deployed the first ICBM. Today, the United States possesses 741 deployed launchers equipped with 1,481 nuclear warheads, while Russia possesses 521 launchers equipped with 1,735 nuclear warheads, bringing the total of the two competitors to 3,216 operational strategic nuclear weapons. To this have to be added, as mentioned, about 2,000 Russian and about 150 American ‘tactical’ nuclear weapons, the latter deployed at bases in Europe.

However, according to scientific estimates, a war of only 100 nuclear detonations would produce 5 billion kilograms of black soot that would rise up to the Earth's stratosphere, block sunlight, produce a sudden drop in global temperatures, eradicate much of the Earth's protective ozone layer, and destroy both land and sea-based ecosystems.

Despite such facts, there is no indication that either of the two nuclear superpowers are in any way aiming at a substantive curtailment of their capabilities. The last US-Russian arms control treaty, the New START concluded in April 2010, allows the two powers to retain up to 1,550 deployed strategic nuclear warheads each. The treaty, however, fails to limit non-strategic nuclear weapons and puts no constraints on modernization efforts. In fact, both countries are in the process of a substantial and costly modernisation programs.

Putin’s Russia took the lead in the planning and implementation of corresponding programs. Their purpose has been made patently clear. The country is to rise again to the status of a Great Power, with ‘greatness’ understood primarily in military terms. As if the Cold War had never ended and Russia were still the Soviet Union, for Moscow’s power elite the point of reference in its military-strategic modernisation programs continues to be the United States. It is striving to maintain strategic parity, now more euphemistically labelled ‘global strategic balance’, despite significant costs and a stagnating economy at rank 13 in nominal terms of GDP behind Italy, Brazil, Canada and South Korea.

Furthermore, Moscow has embarked upon the close integration of conventional and nuclear weapons in doctrine and military manoeuvres. It is, thereby, conveying the dangerous notion that nuclear war is just a mere extension of conventional war and its occurrence a distinct possibility. Such dangerous misconceptions are enhanced by Putin’s return to using nuclear weapons for signalling and threats to enhance Russia’s foreign policy interests.

In fact what we witness is a dangerous restart of a nuclear arms race, as if the Cold War had never ended.